Descartes, ‘Fords, and Les Crampes in Paris

President Emerson and Chancellor Gabriel de Broglie with The Letter

Being a habitually late college student got me a speaking gig — and dyspepsia — in Paris.

I’m totally serious.

The story starts in pre-history when, like all undergrads in Northwestern’s music school, I was miserable. A wannabe rock star with dreams of travel, at NU I felt like a social security number chasing grades, wasting my college years blasting a trumpet in stinky practice rooms.

One day I decided a smaller school back home might be a better place to discover my potential.

In the fall of 1979 I transferred to Haverford College, where I switched to History, hoping it would be good preparation for foreign service, should I luck into that career.

History was hard. I could force myself to write half-decent papers but struggled with dates and names. I earned meh grades and choked on the orals. For years I rued my decision to leave music for a field where I had little ability.

But there was an upside: History majors were required in junior year to take on experiential projects that connected us intimately with the past. The course was History 361, Junior Seminar in Historical Evidence.

Our first assignment was to research a randomly assigned artifact: mine was an old metallic part that joined a railroad tie to the rail. By inspecting it and following a trail that began with an engraved number, I grasped the legacy U.S. patent process in a way I never could have by skimming some book.

The second, more serious task was to select one of several documents the department’s professors had made available from the library’s special collection, then investigate it and write a paper.

The time was set for the History majors to come to the vault to select their documents. I arrived late, as was my habit, and only a handful of documents remained on the table. One was a letter written in old French and Latin cursive. I looked more closely.

It was an original letter written in the 17th century by René Descartes.

You know, Descartes? The really smart dude who penned, “I think therefore I am” and invented analytic geometry? That guy.

I stared at it, probably with my mouth wide open. Seeing I might be hooked, the librarian actually allowed me to pick it up. I had a sudden desire to write a full dissertation.

Then my brain kicked back in.

“Wait a minute,” I thought suspiciously. “Why did all the other History majors pass up this letter? Will this be too much work?”

I expected that the Latin text would be vexing. Fresh, however, from a summer in Quebec pretending to study French, I thought I had at least a foundation to figure out the rest.

In any case, the remaining documents now seemed hopelessly dull by comparison. René was my man. I claimed the letter and left with copies.

As you’ve already guessed, Descartes’s French was in a different league from the conversational Québécois I had learned while under the influence of cidre and crêpes glacées. The subject matter — the Meditations on Metaphysics, which he had been working on at the time of writing — was way over my head. But I dug in.

I had long forgotten the basic Latin I learned in junior high, which wouldn’t have helped me in any case. So I asked for help from a professor on the Classics faculty.

Meanwhile I found a handful of books on Descartes in the Haverford and Bryn Mawr College libraries, including one that cataloged his letters. This one was not among them. Judging from the way the letters were numbered, however, a few must have gone missing; it occurred to me this might be one of them.

I finished the translation as best I could and, in a typical last-minute all-nighter, typed a straightforward paper complete with pen-and-ink edits. The professor who graded it, John Spielman, thought little of my effort and gave it a 2.7 out of 4.0 — in his view a B-minus.

I was disappointed but glad for the experience. My decision to transfer to Haverford College had thus been validated.* I put the letter out of my mind.

31 years passed.

By then my decision to major in History had also been validated: I was a career member of the foreign service, posted at the time to Serbia.

The internet and search engines had meanwhile been invented.

One day in February, 2010 I received an email from someone in Haverford’s public relations office wondering if I was the same Conrad Turner who once wrote a paper on a letter by René Descartes.

I laughed when I read the message. Yes, I replied, that was me.

The next day, a Haverford librarian named John Anderies sent more details:

Greetings from Haverford College Special Collections. I hope my email finds you well. You may recall that when you were a student at Haverford you wrote a paper for History 361 on a letter which resides in our collection from René Descartes to Marin Mersenne. An editor for the new edition of Descartes correspondence has come upon the letter which heretofore had been presumed lost (a fact which you acknowledge in your 1979 paper). He is very excited about this find as its contents “significantly contribute to our understanding of Descartes.” We are both interested in creating a press release about this and I’d like to make sure you receive your due acknowledgement for your work on the letter while a student. Since a copy of your paper resides in our archives, I have taken the liberty of sharing it with this scholar, and he says it is “truly a fine piece of work. Had the author submitted it to a major international journal, it would have been published immediately.” Would you consider being a part of this press release? I think it can only be for the good of Haverford and for scholarship in this field. I look forward to hearing from you soon.

In the exchanges that followed, I learned that Anderies had been posting titles of the library’s special holdings on the internet. When the Dutch cartesian scholar Dr. Erik-Jan Bos was Googling for materials, he saw that Haverford was in possession of a letter and got in touch.

The college’s administration was caught by surprise. Someone ran to the archives to look at the letter in question. They found my 30-year-old paper in the same folder.

Haverford quickly decided to return the letter to l'Institut Français in Paris, whence it had been stolen and sold some 150 years before by some Math professor named Libri. The letter had changed hands several times before being donated to Haverford.

President Emerson planned to hand-carry the letter in June, 2010. I was invited to join the ceremony, which would be followed by an alumni event where I would give remarks.

Haverford was not offering to pay my way, and I was busy with work and family. But this was way too much fun to pass up. I agreed to the trip, and Haverford’s PR office, led by alumnus Chris Mills, began lining things up for the event.

Haverford was in touch with an Associated Press writer, and articles began appearing that included Dr. Bos’s generous praise of my humble work.

Suddenly this low-B procrastinator was being held up as a model ‘Ford.

I struggled a bit with this update to my personal narrative. I had never believed I was “Haverford material,” whatever that meant. It felt strange that a paper I wrote back then would put me in the spotlight.

As a public affairs wonk, however, I knew about storytelling and decided that’s what this interlude would be — a story. Doubts about my abilities notwithstanding, I would play my role helping lead the audience toward a meaningful denouement. Doing so would be important to Haverford, which was doing the right thing and deserved credit. And if my inward story somehow changed as a result, that would be a bonus.

I started getting emails and calls from news outlets wanting interviews. I said no to most of them. One journalist wanted me to send him a copy of my paper. I had misgivings and asked Anderies for advice. He wisely pointed out that academics could be passionate about their fields; there was a chance they would pillory my three-decade-old undergraduate work.

Indeed, on re-reading the paper I saw that my 21-year-old self had judged the letter less important for understanding Decartes’s work than had today’s experts. As for the pre-Google-era translation, it would not stand up to 21st-century public critique.

I turned the journalist down.

Meanwhile, the trip had to be planned. I needed a place to stay in Paris and got in touch with my Haverford roommate, Mark, who was living there with his wife, former Bryn Mawr College student Sheila, and their children. It turned out he was head of the alumni group there and already knew the story. He offered to put me up. I bought my ticket.

I had been to Paris before. The first time was as a long-haired 20-something backpacker. The second was as a Peace Corps trainee on a layover at DeGaulle airport. I had been back a few times as a tourist. In those days Paris seemed frantic and pretentious. I felt out of place.

This trip, however, would be out of a fairy tale. Paris suddenly loomed rich and exotic, and for the next two days, at least, I would feel like I belonged there!

I landed and met Mark at his office — he was a lawyer for a French company — and bought him lunch. Then I took in the Arc de Triomphe and Tour Eiffel with new eyes before heading to a cafe at Montmartre to work on my speech. We left his office together for his home.

It was great catching up with him and Sheila. Their kids were cute: the eldest was into horseback riding, and the youngest, aged 10, was a gymnast. As we chatted, Mark sampled — and I gobbled — two bags of Japanese spicy crackers and lots of gourmet olives.

This would prove a tactical error.

The next morning I donned a suit and tie, went to Starbucks to finish writing my remarks, and began suffering acute intestinal distress from the crackers and olives. I risked a walk to the Latin Quarter and the Pantheon, but by the time I got back to Mark’s office I was having severe cramps.

We drove to l’Institut de France and walked into the library, where a crowd of mostly older men had gathered. The Descartes letter that I had held 30 years before was on display, protected in a small case under glass.

As we walked in, a Haverford alum working for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in Paris grabbed my arm and said, “The press is here, do you want to meet them?”

“No!” I replied.

This was not mere cowardice. I worked with the media all the time for my day job. Now I was in Paris on my own nickel at this fancy gig and just wanted to try to enjoy myself, despite my gut spasms. He dragged me toward the media anyway and left me with a British journalist, who (bless him) wasn’t the least interested in me.

I escaped back into the crowd.

Soon I was introduced to Haverford’s President Steve Emerson and the chairman of the Philosophy department at Erik-Jan Bos’s university. The ceremony began. Full of pomp, it included speeches by des personnes extrêmement importantes including Jean Mesnard, membre de l’Académie des sciences morales et politiques, and Jean-Luc Marion, membre de l’Académie française, who gave a detailed history of the letter.

I thought I heard my role briefly mentioned, though I wasn’t named. My undergrad encounter with the letter, I guessed, must have seemed little more than sacrilege to these austere fellows, whose duty was to protect the great French heritage from riffraff like me.

Emerson gave prepared remarks in passable French and solemnly handed the letter — temporarily removed from its case — to Monsieur Gabriel de Broglie, Chancellor de l’Institut de France, who also spoke. The press took photos. The ceremony ended.

Afterward, I met with Dr. Bos, an earnest young man with wire-rimmed glasses and curly hair, and thanked him for his kind words about my paper which, I said honestly, “wasn’t all that good.”

“No!” he gasped. “You don’t understand. It was really excellent!”

I guessed he had seen a few papers, so I didn’t argue.

Dr. Bos

The ceremony was followed by a cocktail party, where I continued to pretend I was not on the verge of shitting my pants. Then we stepped out into the night, climbed into waiting limos, and raced through Paris to the alumni event.

That was a very cool, dreamy moment — riding in the backseat of a black taxi with Haverford’s vice president, speeding between venues along wide avenues and bridges past gloriously lit buildings. The day had been a funny mixture of history, Parisian beauty, language and culture, French self-importance, Haverford modesty, public relations… and plain absurdity: I was in Paris because of a letter by a dead thinker and a paper I had once typed on an IBM Selectric and annotated by hand. Now I was being spirited through one of the world’s most beautiful cities by important people who were treating me like a prince.

We arrived at Hotel Talleyrand, George C. Marshall Center 2, rue St. Florentin, 75001 Paris — a U.S. Embassy-owned building that had been renovated in recent years with private donations. Though invited, both the U.S. Ambassador and the Minister Counselor for Public Diplomacy — my counterpart — evidently had more important things to do.

The speeches began. Steve Emerson spoke and John Anderies gave a presentation. Then Steve introduced me as “the real hero, though he may not agree with me”.

Feeling drained and now suddenly nervous, I delivered my remarks:

Steve Emerson, Mr. Anderies, Members of the Board, Scholars, Distinguished ‘Fords and guests: while Rene Descartes, Count Libri and “father of the Internet” Vinton Cerf have made today‘s ceremony possible, we have come here because we have a spiritual connection to Haverford, and also of course because many of us happen to live in Europe. It says something about Haverford that a 370-year-old letter is the reason for my trip from Belgrade to Paris, allowing me to visit my senior year roommate Mark Sadoff and his wife Sheila. I have been on the wrong side of the Atlantic and in some cases deep in the Eurasian continent for every reunion for most of the last 23 years, so being part of this one is special for me, and being invited to say a few words is a real honor.

The Turner paper, as it has come to be known, is a footnote in the story of the Descartes letter. But as someone who, as Chris Mills put it, “spent some quality time cuddled up with that document back during the Carter administration,” I’m happy to share some thoughts on what this letter, and its return to l’Institut de France, symbolize. It has to do with the obligation universities have to educate not only their students, but also society at large.

Real education inspires. For too many of the world’s undergraduates, the reality is different. Information is force-fed into the brain, causing a brief rearranging of a few neural networks before being swept off to make room for the next brutal infusion of facts. What remains is a grade on a transcript. Inspiration, on the other hand, turns the brain into a magnet not just for facts but reason, purpose and values. That is what makes the difference between a good college and a great one.

The other day I spoke to Serbian university students about Diversity in the United States. Students there complain that professors lecture at them while keeping a studied distance. They’ve learned to expect worse from foreign diplomats, so I love to smash those stereotypes: as I addressed those students I paced the room, stepping forward and back, gesturing, asking open-ended questions, encouraging a lively give-and-take… In other words, I worked hard to inspire them.

Some of you will recognize a style mastered by Professor Emeritus Roger Lane. I sat quietly during his year-long American History course, but that didn’t prevent me from admiring, and one day imitating, his inspirational teaching style. It just seemed like the right way to do it. (I don’t mean to contradict myself, and please don’t tell Roger, but that’s the only thing I remember from his class.)

As a student then I thought it bizarre that some people could get worked up over the Honor Code. What was the big deal? Yet 21 years later I was on the lecture circuit, addressing thousands of students at a dozen universities in Kyrgyzstan on the subject of academic integrity, helping them write honor codes, and leading seminars using abstracts provided by Haverford’s Honor Council. Concepts that seemed pretty mundane to me as a student turned out to be excellent tools for helping universities, through their students, to come to terms with problems that threatened their country‘s development.

And then there’s the Descartes letter, which over a few weeks forced a sleepless young man to think of the great philosopher and mathematician as a real human being.

It’s not unusual for a student to see the extraordinary as ordinary, as I did the Honor Code, Roger Lane, and even exclusive access to an original letter penned three centuries ago by one of mankind‘s greatest thinkers. And really, isn’t that a goal of education? We should enter the workforce taking for granted that inspiration and integrity are the ideals we’re supposed to strive for. Embracing these values is what grounds us throughout our careers, as we engage in the struggle between our desire to hold to the values of our profession, and our need to navigate the politics governing that profession.

This struggle is evident in the letter itself, which if you read between the lines is really a scene from a political drama. Descartes’ challenge was to be true to scientific values while avoiding offending the religious figures who could have been his undoing. It wasn’t easy, and makes you wonder where he got his inspiration and integrity.

My stories from Haverford days are only a small part of the picture, and I’m sure many of you have similar ones. But colleges have a responsibility to educate that transcends even their duty toward their students. Returning the Descartes letter to its owner should be an obvious step. We might even take it for granted. Others do not. A close colleague of mine, whose opinions I respect, was incredulous when I shared the news. “Why give it away? Who cares how it got there, it’s Haverford’s now.” I understand this point of view. Many people would agree, maybe a majority. It was stolen a long, long time ago, and stuff happens.

But stuff doesn’t just happen. We make it so, as individuals and as institutions. Seen in another way, Haverford’s power to confer a prestigious degree carries certain rights and privileges, as well as obligations. Just as I was allowed 31 years ago to connect with history by staring at original ink marks, a great college must be aware of its historical role, and through its actions improve on history by taking a public stand on behalf of integrity. In this case, Haverford’s obligation – to educate us by inspiring us – was simply to do the right thing and return the letter to its home, giving up any perceived benefit the college might have had by clinging to it.

And your decision has inspired us, the news rippling through academic networks worldwide in multiple languages, all the way to my daughter’s high school in Belgrade, where the librarian, on learning my humble connection to the story, gaped at me as if I were a rock star and said, “That was you?”

My audience exploded in laughter. Guests raved about my speech afterwards. Someone said, “You are a rock star.” Someone else called me a “poster boy for Haverford”. Another said I really captured what Haverford is about. One tall, Quakerly-looking gentleman from the Board of Trustees looked very serious and pensive as he praised my remarks.

Holy cow. I was relieved. Even my bowels found peace with the previous day’s spicy onslaught.

A Haverford Philosophy professor approached me sheepishly, saying she had wanted to meet with me: it was she who had been called in to verify that they were indeed in the possession of an original Descartes letter: In fact it was my paper next to the letter, she said, that helped her to identify it. She also passed regards from the Latin professor who had helped me with translations back in 1979. (I have since noted that I failed to credit said professor, whose name I don’t recall, in the paper.)

It was still awkward to hear myself presented as some kind of model, considering how out-of-place I had felt as a student. I confessed as much to another alumnus at the event, saying how overwhelmed I was at the time at how smart everyone else seemed. He assured me he had felt the same.

As the reception wound down, Mark congratulated me. I admitted to him wryly that Spielman had only given me a 2.7 on my paper.

He quipped, “Well, now you got a 4.0!”

Dinner was at Restaurant Le Procope, where Benjamin Franklin reportedly once dined. I was still the center of some attention. A member of the Board even suggested I apply for a position as Executive secretary at the Friends’ Committee on National Legislation.

Those seated at my table included two Haverford professors, who debated whether it was necessary today for students to learn a foreign language. Having spent years learning hard languages, I was appalled that this was even being discussed.

The next morning my Parisian fairy tale was over. I headed home and went back to being a bureaucrat in Belgrade.

Later I sent Erik-Jan photos from the evening, and he wrote me this wonderful message:

Thank you so much for the photos; I had not seen any photos of the gathering yet except for the few ones in the media. When Emerson told me that you were there too, I actually was more happy about that than to see the letter; I had seen the letter, read it, but it does not talk back to me. I found it very interesting and gratifying to talk to those who have an intimate knowledge of the letter, that is you and John Anderies. Somehow that old piece of paper brought us together, and I enjoyed every minute of it. I’d be grateful for any more photos; when I have deciphered what is written on the back, I will let you know.

He was referring to a picture one of us had taken of the reverse side of the letter, which had mysterious writing on it. I digitally inverted it and sent it back to him. He responded that the words were, “Cette addresse est de la main de Descartes” [this address is in Descartes’ handwriting.] “Unfortunately,” he wrote, “no secret message from Descartes himself.”

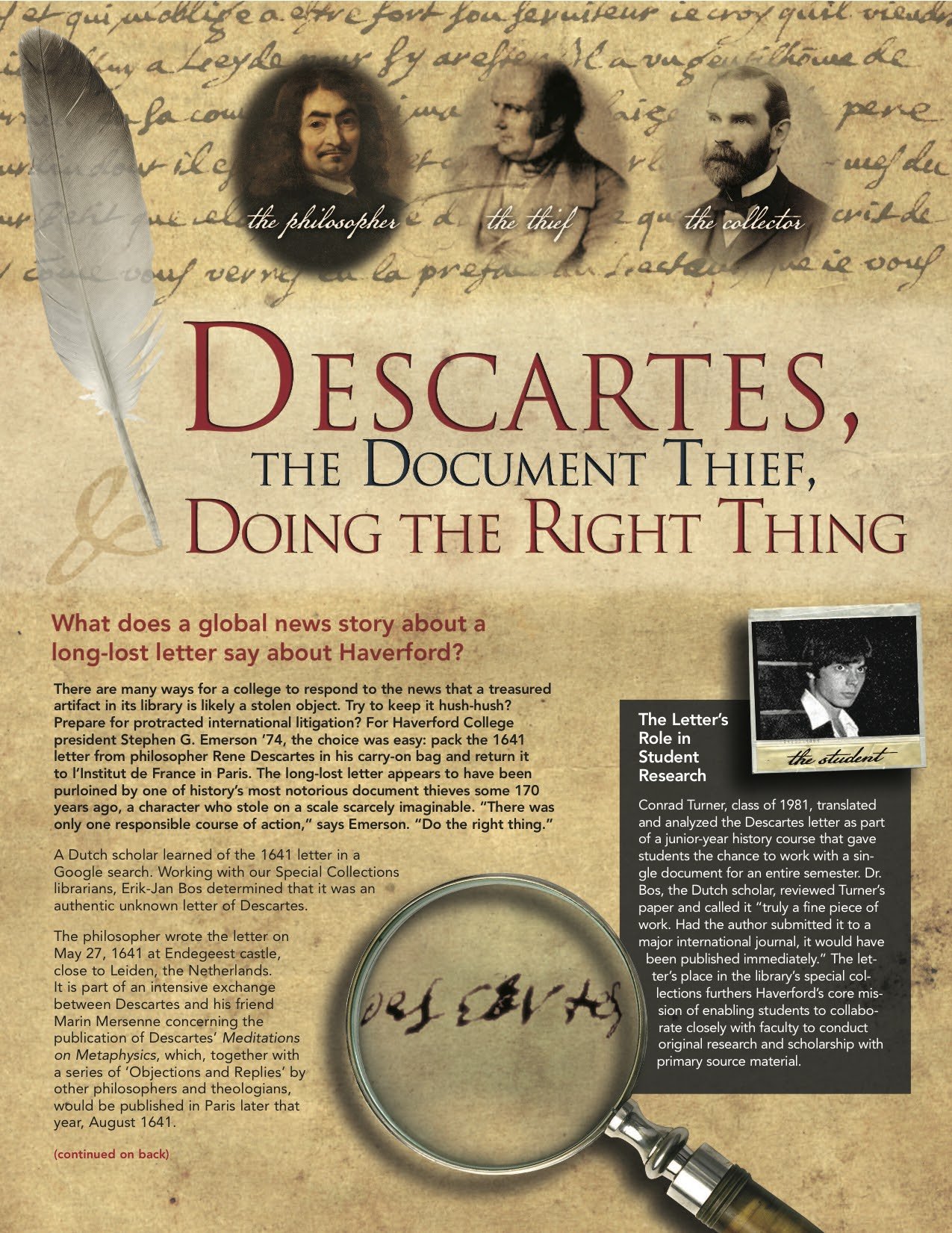

In the following months, Haverford published my speech on its website. They also produced flyers, which my daughter, who was applying to Haverford, and I saw stacked for prospective students in the admissions office when we came for her interview. Entitled, “Descartes, The Document Thief, Doing the Right Thing,” it told the story of the letter and its return to its rightful owner.

It included an excerpt from my paper and a nighttime yearbook photo from a set my friend Drew took of me thirty years earlier. I had long, thick hair and was wearing a white shirt with an open, wide collar, and I gazed mysteriously into the distance, looking like a young detective.

But here’s the truth: I was just a college kid who wanted to be a rock star.

Photo by Drew “Noopers” Vaden

*I’ve been around, and there simply is no finer institution of higher learning than Haverford.